India’s Semiconductor Future Lies with Its Small Manufacturers- The Untold Equipment Story

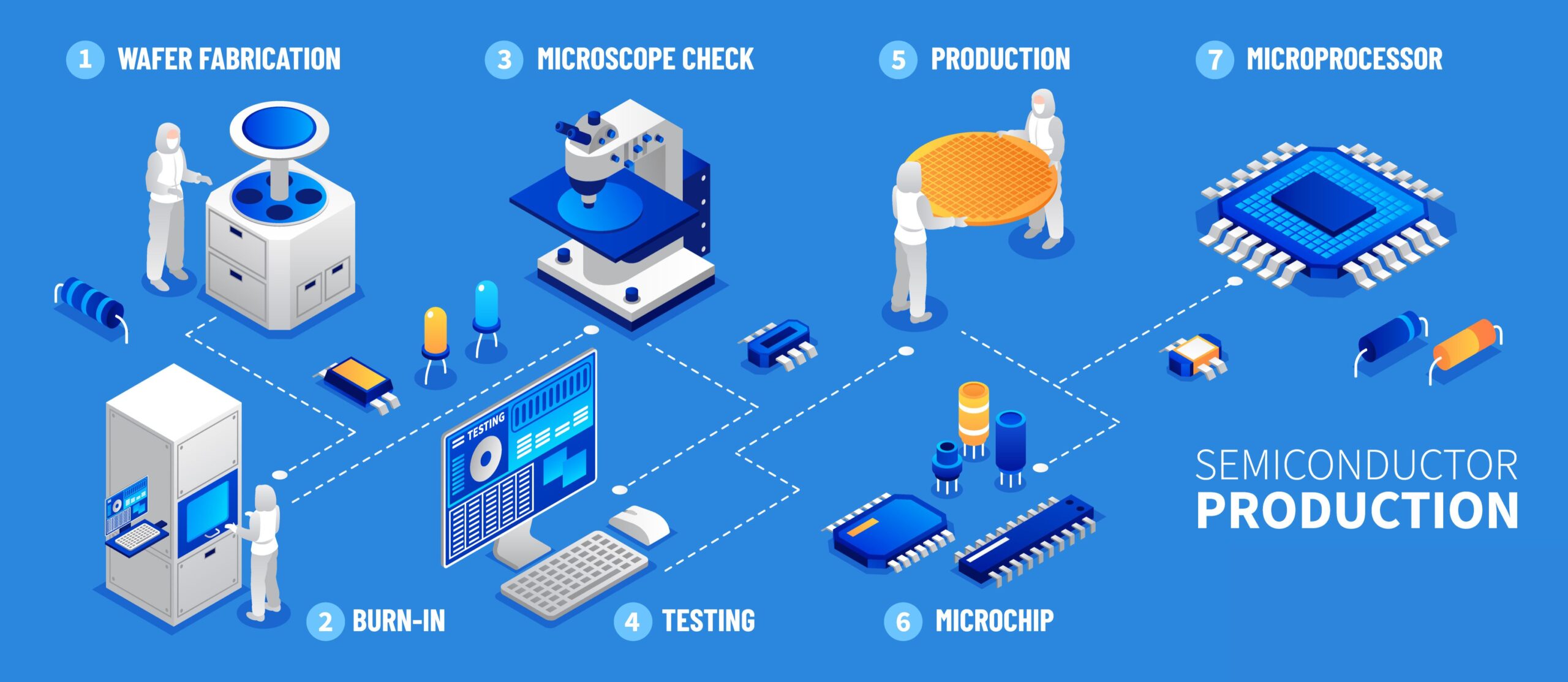

India’s semiconductor dream is often described through giant fab plants, billion-dollar incentives and global tech partnerships. But the real story rarely told is this no nation becomes a semiconductor power by building fabs alone. The real sovereignty lies not in making the chip, but in making the machines, tools, gases, robotics and precision parts that make the chip possible.

And here lies the opportunity and the missing link for India’s manufacturing MSMEs.

From Fab Ambitions to Equipment Reality

India has announced over $10 billion in incentives for semiconductor fabrication plants (fabs) and chip assembly units. Companies like Tata, Micron, and Foxconn have begun their journeys. Yet, more than 80% of semiconductor equipment lithography machines, etching tools, wafer handling robotics, vacuum systems, plasma cleaners, deposition and testing machines are still imported from just a handful of nations: the U.S., Netherlands, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

This means even if India manufactures chips, it will still depend on foreign technology for the most critical part of the value chain semiconductor-grade machinery.

Where MSMEs Fit into This Billion-Dollar Gap

India already has thousands of precision engineering MSMEs working in automotive, aerospace, defence and medical devices. These companies build high-speed spindles, CNC tools, lasers, optical components, cleanroom assemblies, vacuum pumps, robotics and mechatronics all foundational to semiconductor equipment manufacturing.

Some examples of how this ecosystem is quietly evolving:

- Sahajanand Laser Technology (Gujarat) has begun supplying laser machinery used for wafer marking and micro-cutting.

- Tata Group’s semiconductor OSAT project in Dholera is onboarding tier-II suppliers from Pune, Coimbatore, Hosur and Rajkot for tooling, metal fabrication and thermal components.

- SCL Mohali and ISRO labs are working with local MSMEs to refurbish imported machines to understand process technology from inside the black box.

This is India’s strategic opportunity if nurtured correctly, MSMEs can become the backbone of semiconductor equipment manufacturing, not just spectators in the chip boom.

What Global Chip Hubs Did Differently

India doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel the semiconductor superpowers wrote this playbook decades ago.

Countries like Taiwan, South Korea and Japan didn’t become semiconductor giants by only building fabs they built SME-driven supplier networks around them. Taiwan focused early on training local precision manufacturers through ITRI to make components for chipmaking tools like photolithography and testing machines. Today, nearly two-thirds of the parts used in TSMC’s fabs are sourced from domestic SMEs that specialise in optical equipment, automation systems and ultra-fine machining.

South Korea took a cluster-based approach. Companies like Samsung developed supplier parks near their fabs, where small manufacturers were trained to produce gas modules, wafer handling systems and cleanroom robotics. These SMEs later became export-ready, reducing Korea’s reliance on imports while supplying globally.

Japan carved a niche in semiconductor equipment components rather than chips themselves. Through strong industry-academia collaboration, small firms mastered vacuum pumps, plasma chambers, high-purity ceramics and lithography subcomponents. This allowed Japan to dominate the upstream equipment value chain, proving that chip leadership is built on micro-engineering excellence not just big factories.

India has begun similar moves through SAMARTH (Semiconductor and Display Fab Equipment R&D), the Digital India Future Labs, and ₹760 crore design-linked incentives (DLI). But MSME participation must move from theory to execution.

A 3-Phase Roadmap for India’s Equipment Ecosystem

Phase 1: Foundation

- Create semiconductor-grade training for MSMEs in vacuum engineering, robotics, micro-tooling, contamination control.

- Convert existing clusters (like Rajkot, Sriperumbudur, Peenya, Jamnagar) into cleanroom-certified precision hubs.

- Enable joint R&D cells between IITs, CSIR labs, and tool making MSMEs.

Phase 2: Scale & Industry Clusters

- Set up Semiconductor Equipment Parks with shared prototyping labs, Class 100-1000 cleanrooms, laser fabrication units, gas management systems.

- Allocate credit support and tax waivers for MSMEs making semiconductor-grade equipment, ceramics, metal parts and gases.

- Introduce a “Semiconductor Equipment Development Fund”, like Taiwan’s ITRI and Japan’s METI models.

Phase 3: Global Export & Strategic Depth

- Start exporting India-made tools to Southeast Asia, Middle East and Africa.

- Build domestic capability in advanced machine segments wafer bonding, plasma etching, PVD/CVD tools, lithography sub-modules.

- Train workforce in critical areas: RF electronics, cryogenics, plasma dynamics, optical mechatronics.

New Risks, New Skills What Must Change for India to Win

Building fabs is capital-intensive; building equipment capability is knowledge intensive. This challenge is not just technological it is cultural.

- Talent Gap: India only has around 5,000 engineers trained in semiconductor equipment engineering vs. China’s 40,000.

- High-Purity Materials: Ultra-high vacuum metals, semiconductor-grade chemicals, and specialty gases (like nitrogen trifluoride) are still nearly 100% imported.

- R&D Funding: India spends less than 0.7% of GDP on R&D; Taiwan spends 3.6%, Korea 4.5%.

Unless MSMEs enter this value chain, India risks being an “assembly nation”, not a technology nation.

The Window of Opportunity

The global chip industry is undergoing a historic reset U.S.-China tech rivalry, friendshoring, supply chain security and AI-driven demand have created a once-in-50-years opportunity.

If India responds by empowering its machine tool makers, material suppliers and MSMEs, it can become not just a chip manufacturer, but a trusted equipment partner to the world.

But if it builds fabs without machines, it will remain dependent, vulnerable, and replaceable.

Semiconductor self-reliance is not about making chips. It is about making the machines that make chips. And that future will be powered by India’s small manufacturers.