Critical Minerals: The New Nerve of India’s Industrial Resilience

In 2025, India’s manufacturing and export-financing sectors are navigating an increasingly tense geopolitical landscape one defined not by oil or semiconductors, but by critical minerals. As the global economy pivots toward clean energy, digital infrastructure and advanced manufacturing, minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, copper and rare earths have become the invisible currency of industrial power. Yet, the concentration of their supply and China’s entrenched dominance in processing has made this resource base the newest fault line in global economic security.

India’s policymakers have begun to grasp the magnitude of the challenge. With battery manufacturing, electric vehicles, renewable energy and electronics forming the backbone of its next industrial leap, ensuring uninterrupted access to critical minerals is no longer just an issue of trade it is a question of national capability.

Why Critical Minerals Matter

Modern industrial ecosystems depend on mineral inputs in the same way earlier economies depended on oil. Lithium and cobalt power electric mobility; copper and nickel run through the wiring of renewable grids and electronics; and rare earths form the core of magnets used in everything from turbines to smartphones. Yet, most of these materials are not refined or processed within India. A disruption in a single supply corridor can raise input costs, delay production and undermine export reliability for entire sectors.

The International Energy Agency’s Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025 warns that despite two years of price corrections; supply concentration remains dangerously high. China continues to dominate refining and processing across the value chain, while new projects in Africa, Australia and Latin America will take years to become fully operational. For India, which is scaling up electric mobility and semiconductor manufacturing at unprecedented speed, this exposure is a structural risk.

India’s Mission-Mode Response

Recognizing this vulnerability, the Indian government has launched an ambitious policy framework anchored by the National Critical Mineral Mission, approved by the Union Cabinet earlier this year. With an allocation of ₹34,300 crore over seven years including ₹16,300 crore in direct expenditure and ₹18,000 crore in PSU investment the mission spans the entire life cycle of mineral development, from exploration to processing and recycling.

At its core is an empowered inter-ministerial committee chaired by the Cabinet Secretary, tasked with coordinating a “whole-of-government” approach to reduce import dependence and secure long-term supply. Complementing this is the proposed National Critical Mineral Stockpile, envisioned as a two-month buffer reserve of rare earths and other high-value materials. The stockpile will serve as a strategic shock absorber against export curbs or geopolitical disruptions, while inviting private-sector participation in its management.

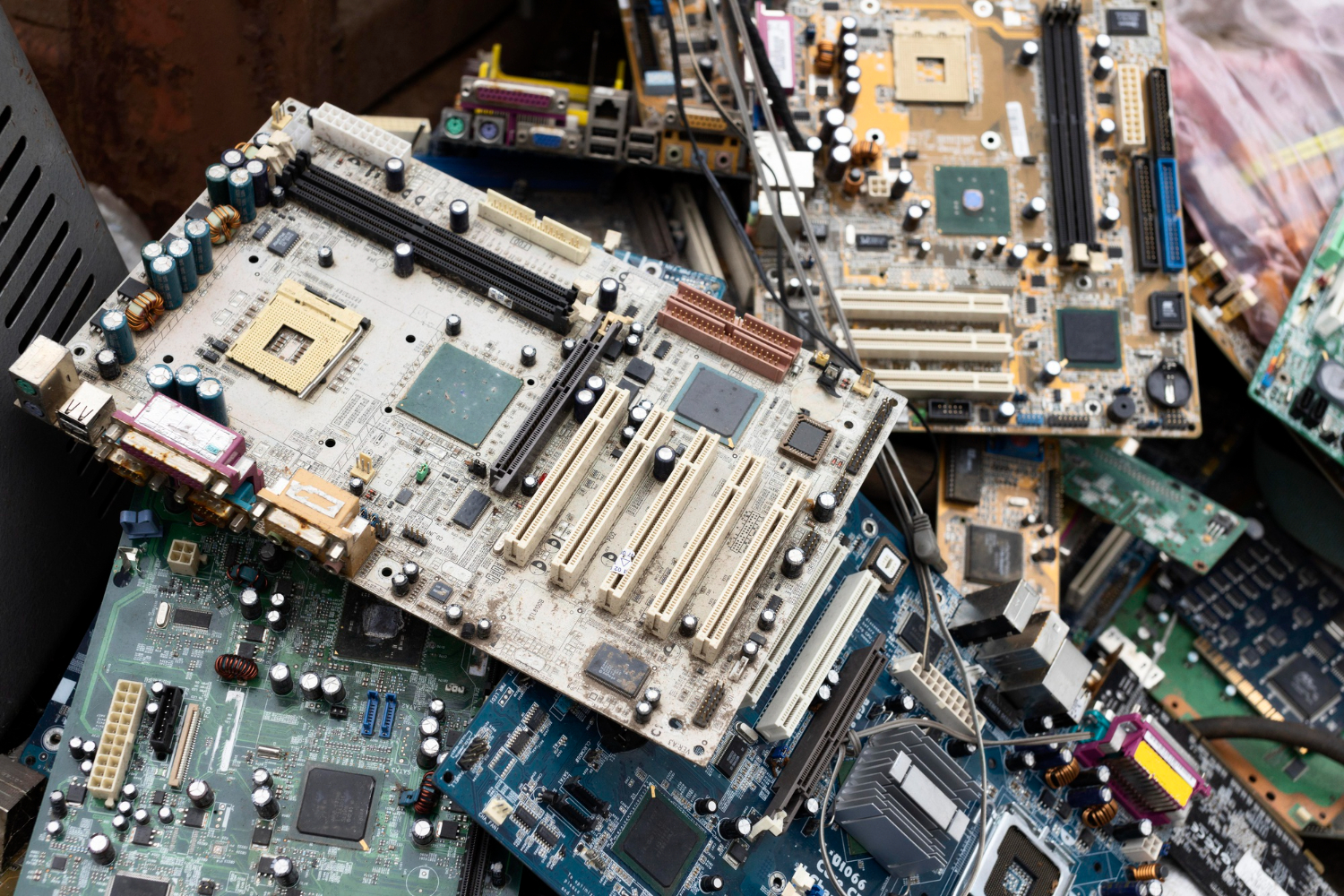

Parallel initiatives, such as incentives worth ₹7,300 crore for domestic rare earth magnet production and a push to recover valuable materials from e-waste, indicate a shift from crisis response to ecosystem building. Together, these policies could form the foundation of India’s mineral self-reliance architecture through 2030.

Global Geopolitics: Positives and Negatives

Recent policy coordination among the G7 under the Critical Minerals Action Plan has created new opportunities for diversification, co-investment and recycling partnerships tracks in which India is increasingly engaged. Broader awareness of supply risk among major economies is accelerating project pipelines and joint ventures, creating optionality that Indian firms can leverage through offtakes, equity stakes or tolling contracts across friendly jurisdictions.

On the other hand, China’s export restrictions on rare earth magnets and its entrenched dominance in refining keep a persistent risk premium on critical inputs. Public data show that Beijing controls roughly 60% of global rare earth mining and up to 90% of refining a degree of concentration unmatched in any other industrial supply chain. For India, this reality underscores that any escalation in trade tensions or diplomatic frictions could instantly translate into manufacturing and financing shocks.

The recent Trump-Xi summit in Busan (October 2025) has added a fresh, if temporary, twist to this dynamic. According to official readouts, both leaders agreed to a one-year moratorium on new export curbs related to rare earths and battery metals, alongside a tacit understanding to “stabilize” global supply chains. Markets welcomed the move, with rare-earth spot prices easing slightly in the days that followed. Yet beyond the optics of détente, little has changed in structural terms. China still controls the majority of global output and nearly nine-tenths of refining capacity, meaning the fundamental imbalance and India’s exposure remains.

For New Delhi, the Busan understanding is both an opportunity and a warning. It provides short-term breathing space to secure offtake agreements and accelerate stockpile implementation but also reinforces the urgency of diversifying away from China’s processing dominance. A single policy reversal in Beijing could undo months of supply stability. Hence, India must use this window to finalize long-term sourcing arrangements in Africa, Latin America, and Australia, operationalize its mineral stockpile, and strengthen ties with allied frameworks such as the G7 plan. The Busan détente may delay turbulence, but it does not eliminate it.

Implications for Indian Manufacturers and Financiers

For India’s OEMs and Tier-1 suppliers in electric vehicles, electronics, renewables and magnets, the mission-plus-stockpile framework reduces systemic exposure but does not eliminate risk. Companies must adopt procurement diversification and inventory strategies that extend beyond short-term hedging. Mapping sub-tier dependencies especially in refining and precursor materials has become essential. Disruptions rarely start at the mine; they begin in processing hubs, where geopolitical leverage concentrates.

Banks and trade financiers, too, must adapt. Supply disruptions can create borrower cash-flow volatility, project retimings, and collateral value swings. Credit models must now account for upstream jurisdictional risk, offtake tenors and ESG compliance factors increasingly tied to global co-financing. Blended finance and contingency liquidity lines can cushion potential shocks, while early-warning systems tracking export-control rumours or logistics shifts can pre-empt exposure escalation.

The Road Ahead

India’s path to becoming a manufacturing and clean-tech powerhouse runs through the corridors of mineral security. The new policy architecture combining mission-mode reforms, strategic stockpiles, and international coordination signals a pragmatic blend of industrial strategy and risk governance. But success will depend on how effectively government, industry and financiers translate policy intent into operational resilience.

The lesson from Busan is clear: in the new resource geopolitics, diplomacy can buy time, but only domestic capacity can buy security. For India, resilience in critical minerals is no longer optional it is the foundation of industrial sovereignty.