India’s electronics moment: from assembly lines to strategic supply chains

India’s electronics story has shifted from promise to performance. The twin headlines of the moment smartphone exports hitting a monthly record of roughly $1.8 billion in September and the government’s first seven approvals under the Electronics Component Manufacturing Scheme (ECMS) worth ₹5,532 crore are not anecdote and policy respectively. Together they map a trajectory: policy incentives are being translated into capacity, and capacity is being converted into trade and jobs. For business leaders and SMEs, the question is no longer whether India can scale electronics manufacturing; it is how to convert this momentum into durable competitiveness that spreads beyond headline factories into thousands of smaller supplier firms.

A Sector That Has Crossed the Tipping Point

The data is unambiguous. Electronics is now among India’s top export categories: H1 FY26 electronics exports were reported at about $22.2 billion, mobile production rose to ₹5.45 lakh crore in 2024–25, and exports of mobile phones have expanded exponentially over the last decade. ECMS commitments, reported at over ₹1.15 lakh crore to date and with projected production and employment far exceeding initial targets, indicate the government’s intention to move upstream from finished product assembly to indigenous component fabrication. That matters because components are where value, technology and margins increasingly concentrate.

Why components matter to the SME ecosystem

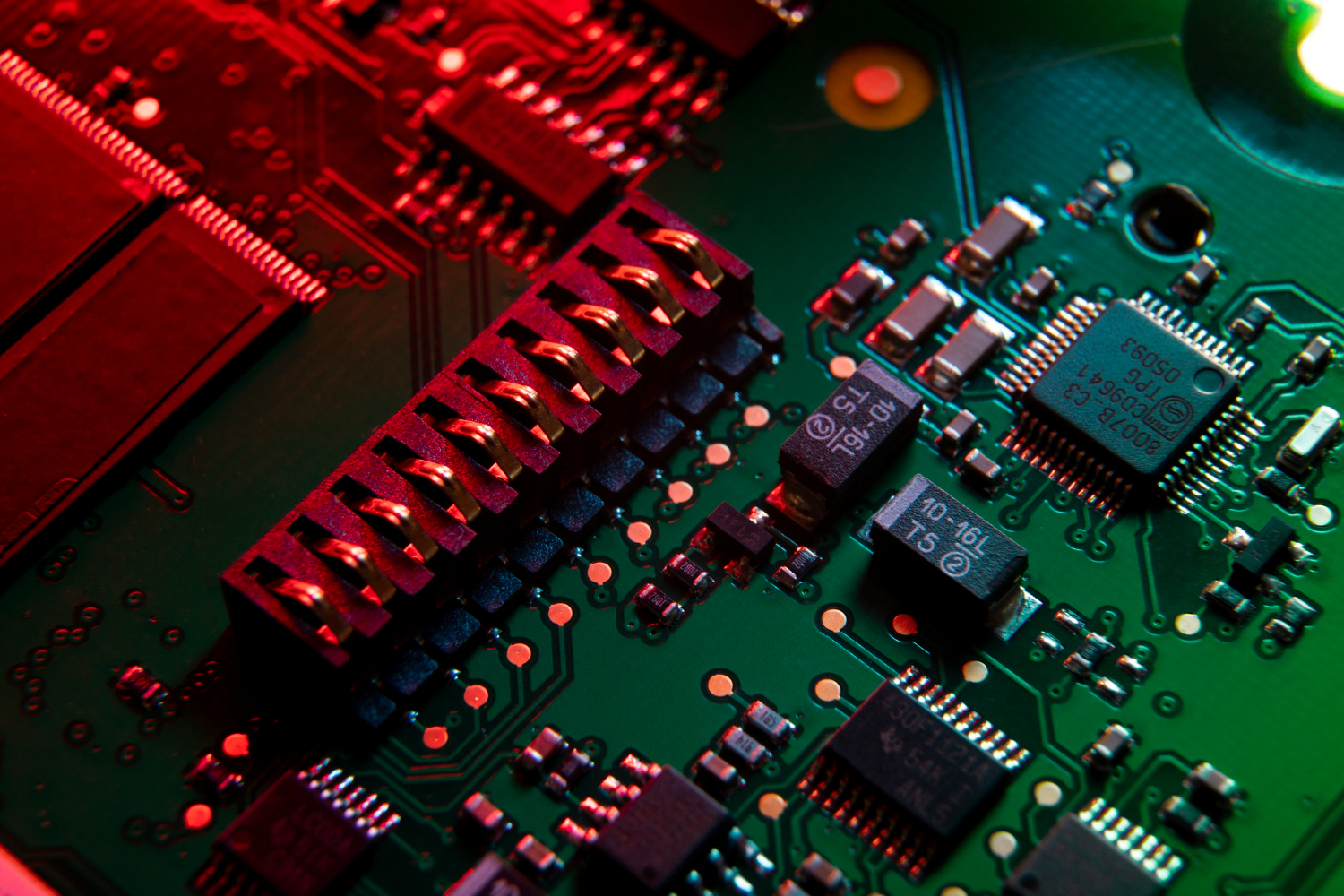

Large contract manufacturers and global OEMs attract attention and rightly so but the industrial reality is that a smartphone is only as export-ready as its ecosystem of PCB houses, camera-module assemblers, laminates producers, capacitor film suppliers and test-and-certification labs. These are overwhelmingly SMEs. Their ability to meet global quality standards, manage just-in-time logistics, and demonstrate compliance on provenance and sustainability will determine whether India’s factories become permanent nodes in global value chains or remain episodic, policy-driven bursts of activity.

The ECMS approvals for camera module sub-assemblies, HDI and multi-layer PCBs, laminates and polypropylene film are therefore significant. They target precisely the inputs that nations with mature electronics ecosystems either produce domestically or import under controlled, high-value supply chains. Building this supplier base reduces dependence on single-source geographies, shortens lead times and improves the bargaining power of Indian manufacturing clusters.

Trade, geopolitics and the new calculus of supply chains

The global trade environment is in flux. Firms are diversifying supply chains away from concentrated geographies for reasons that are as much commercial as strategic: geopolitical friction, export controls and the desire for resilience. This creates a genuine window of opportunity for India. Recent FTAs and trade agreements as well as ongoing negotiations matter because market access de-risks export strategies. Preferential tariff treatment, clearer rules of origin and predictable regulatory frameworks make the economics of exporting from India far more attractive, particularly for SMEs operating with thin margins.

But trade policy is only one side of the coin. Strategic conversations now routinely tie industrial policy to national resilience. Local production of critical sub-assemblies has defence, healthcare and energy-security implications. The policy architecture that incentivises component manufacture must therefore be paired with practical facilitation: expedited testing and certification, predictable logistics corridors and financial products aligned to the cyclical cash needs of suppliers.

Operational hurdles that need candid fixes

Conversion of approvals and headlines into commissioned plants and orders will depend on practical execution. Three operational bottlenecks deserve priority attention:

- Working capital and receivables finance: SMEs repeatedly cite cash-cycle stress as the primary constraint. Finance instruments that blend term funding for capex with receivables-backed lines will be crucial.

- Standards and testing infrastructure: Export readiness is as much about trusted certifications as it is about production volume. Accelerating labs and recognised testing facilities inside cluster geographies reduces time-to-export.

- Skills and shop-floor discipline: Advanced component manufacturing demands precision engineering and process maturity. National and industry skill partnerships must deliver technicians and supervisors fluent in modern assembly and quality protocols.

Why this moment is different

Two factors distinguish today’s momentum from previous manufacturing spurts. First, there is supplier density. Where earlier India imported many intermediate inputs, the pipeline now shows organised investments into PCBs, camera modules and laminates the building blocks of higher-value manufacturing. Second, global buyers are actively seeking diversification. Investment is not merely chasing low cost; it is prioritising predictable compliance, geographic hedging and supplier transparency. India’s gains will be durable if the nation converts factory starts into long-term supplier contracts that sustain volumes even when incentives taper.

The role of policymakers and business leaders

Policymakers must focus on implementation: make cluster land and utilities bankable, simplify compliance at the district level, and link incentives to measurable supplier development outcomes. Trade negotiators should prioritise pragmatic clauses that reflect the realities of complex value chains not only tariff lines but origin rules, standards harmonisation and dispute remediation mechanisms. Business leaders, especially at OEMs and large assemblers, should see supplier investment as strategic: finance capability-building for key vendors, co-invest in testing facilities and commit to multi-year offtake arrangements that allow suppliers to expand with confidence.

A human-centred industrial transition

Finally, this expansion is not abstract economics; it is jobs, livelihoods and skills evolving in real places. The ECMS approvals promise thousands of direct jobs and many more indirect ones across labour-intensive and technical roles. Bringing SMEs into export value chains creates pathways for local prosperity that go beyond wage labour ownership of IP, higher-skilled work and managerial capability.

India has the policy architecture and now a growing industrial depth. The near-term task is operational: turn approvals and record export months into sustainable supplier ecosystems, resilient trade linkages and inclusive employment. If this execution succeeds, India will have done more than increase production it will have rewritten how it participates in the global electronics economy. That outcome is commercially valuable and strategically important; for SMEs, it would be transformational.