NaBFID–APCRDA Pact Signals Infrastructure Boom in Amaravati: Andhra SMEs Must Gear Up for Capital Transformation

By all accounts, the recent MoU signed between the National Bank for Financing Infrastructure and Development (NaBFID) and the Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority (APCRDA) marks a significant moment in India’s urban future. Backed by the renewed leadership of Chief Minister Shri N. Chandrababu Naidu, the effort to breathe life back into Amaravati as a greenfield capital city is more than an infrastructure plan it’s a bold attempt to restore economic imagination to the heart of Andhra Pradesh.

But even as government agencies align, one question remains unresolved:

Can Andhra’s small and medium enterprises its builders, vendors, service providers find a place in this new chapter? Or will history repeat itself, leaving them as spectators to someone else’s skyline?

A Capital Project That’s Not Just About Capital

The NaBFID–APCRDA agreement outlines a roadmap that includes financial modelling for urban infrastructure, unlocking land assets for monetisation, structuring revenue-generating projects and attracting large investors through Public-Private Partnership models. Amaravati, in its latest iteration, will not be a scattershot experiment. It will be anchored in professional capital strategy the kind NaBFID was created to deliver.

It’s not the first time such ambitions have been sketched. But this time, the foundation appears less ornamental. NaBFID brings a track record of supporting over ₹30,000 crore worth of infrastructure pipelines across India and with the central government pushing for ₹100 lakh crore in infrastructure investment under the National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP), Amaravati could find itself in the right orbit if it plays its cards right.

This opens up a real, practical opportunity for local businesses. Not just in construction and materials, but in the broader ecosystem of urban development.

Sectors That Stand to Gain

If Amaravati is to become a smart, sustainable, service-driven city, as envisioned, its growth will touch a diverse set of sectors many of which already have a strong SME presence in Andhra Pradesh.

Take building materials and construction services, where districts like Krishna and Guntur have hundreds of mid-sized players with legacy expertise in tiles, cement and modular units. Or electrical and mechanical subcontracting, where Andhra firms have supplied components to everything from SEZs to housing projects in Hyderabad and Chennai. These are businesses that know how to deliver but have often lacked access to structured contracts or institutional partnerships.

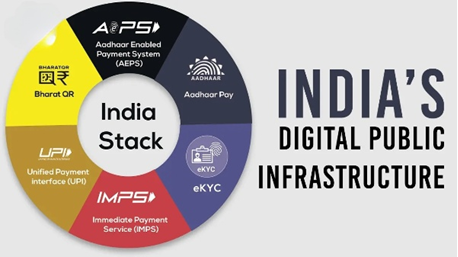

Then there’s the rise of urban services waste management, water treatment, digital utilities and mobility infrastructure where small firms are beginning to deploy technology-driven solutions. Andhra’s IT-enabled services base, particularly in cities like Vijayawada and Visakhapatnam, is also quietly expanding its footprint into civic-tech applications, many of which could align with Amaravati’s new vision.

Let’s not forget logistics, especially cold-chain and last-mile solutions, where SMEs in the state are already plugged into agriculture and pharma supply chains. With Amaravati positioned as a future administrative and commercial hub, these networks could evolve into fully integrated service corridors provided planning accounts for them.

Why Local SMEs Still Struggle to Get In

Despite the breadth of opportunity, barriers for SME participation remain entrenched and, in many ways, unchanged since Amaravati’s earlier attempt at transformation.

Many SMEs are still unable to participate in public tenders due to incomplete documentation, weak financial books or poor credit histories. Others are deterred by the delayed payment culture that plagued earlier contracts in Amaravati’s Phase 1, leaving dozens of local contractors and vendors with unrecovered dues and idle machinery.

The problem isn’t just administrative. It’s structural. Most SMEs in the region operate without financial buffers and struggle with the upfront capital or performance guarantees that larger infrastructure projects demand. When the state pauses or policy shifts occur as happened in 2019 it is the small businesses that absorb the shock.

There is also a visibility gap. Government agencies often release project tenders in formats and timelines that SMEs find hard to track or decode. The lack of proactive engagement between industry departments and local business chambers further adds to the disconnect.

What Must Change

To make Amaravati work not just as a capital, but as an inclusive economic engine both the state and its SME ecosystem need to make meaningful adjustments.

From the government’s side, this means breaking down large infrastructure contracts into modular packages where SMEs can bid as independent entities or consortium partners. It also means enforcing strict payment timelines, creating a dedicated grievance redressal mechanism and offering technical assistance for SMEs navigating complex tenders.

But SMEs, too, need to move. They need to shed the low-risk, low-formality mindset. They must embrace standardisation, digitise their operations, and build consortiums that improve their delivery capacity. Andhra Pradesh already has a few success stories micro clusters in Prakasam’s granite sector or Guntur’s logistics base that show how SMEs can punch above their weight when they coordinate and formalise.

Most importantly, SMEs need to start showing up to policy conversations. Urban infrastructure today is not just about steel and cement. It’s about governance models, data integration and resilience planning. If SMEs are not part of the conversation, they won’t be part of the execution.

A Look Across the Border

While Andhra prepares to restart Amaravati, other states have quietly built momentum.

In Karnataka, Bengaluru’s suburban rail and mobility corridors are drawing in Tier-II tech SMEs who are offering solutions around e-ticketing, fleet management and predictive maintenance. Uttar Pradesh’s New Noida initiative, backed by the Jewar airport corridor, is building pre-planned industrial zones with defined SME participation models and plug-and-play infrastructure. Meanwhile, Tamil Nadu is leveraging its land pooling and policy incentives to create peri-urban SME manufacturing zones with embedded urban infrastructure support.

The contrast is clear. Other states are embedding SME ecosystems into infrastructure blueprints, not leaving them to scramble afterward. If Andhra wants Amaravati to thrive, it cannot treat SME involvement as an afterthought.

The Real Risk

The NaBFID–APCRDA MoU represents a second chance not just for Amaravati, but for the idea that local enterprise should be part of state-building. It signals a shift from political symbolism to financial discipline. But that shift will mean little if the people who build, transport, service and supply the SME backbone are once again kept at arm’s length.

This time around, there’s no room for romanticism. Amaravati will succeed if it delivers value to its residents, jobs to its workers and returns to its investors. SMEs have a role in each of these. But only if they and the system are prepared to meet each other halfway.

Because in India’s infrastructure journey, capital cities aren’t just made of masterplans. They are made of contractors, coders, vendors and risk-takers. Amaravati’s future, too, will be written by those willing to stay, build and adapt.